The ultra-cold temperatures needed for epic nuclear science

Alamy

AlamyOne of the world's most sophisticated scientific facilities is turning to ultra-low temperatures to try and unravel hidden secrets of our Universe.

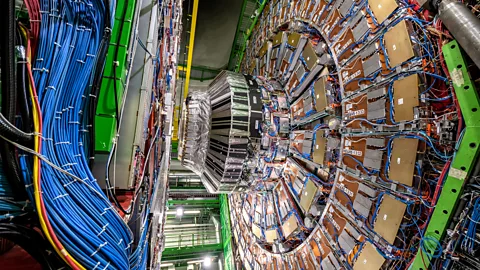

It's one of the most famous scientific installations in the world – and it's getting a cool upgrade. Physicists use the Large Hadron Collider (LHC), buried in the ground on the border between France and Switzerland, to unravel secrets of the tiny particles that make up our Universe. The LHC works by smashing some of these particles into one another and observing what happens when they collide.

By the 2030s, the LHC – built by the European Organization for Nuclear Research (Cern) – will produce many more of these collisions. The idea is to obtain even more precise measurements of the subatomic particles that result in those impacts. Should any measurements ever deviate from values defined by the so-called Standard Model of physics, then, "we'll know there must be some new physics," says Martin Aleksa, technical coordinator of the Atlas experiment at Cern. "This is the big goal of LHC."

But, surprisingly, this pioneering research probing the intricacies of matter itself depends, at least in part, on technology that is also used in supermarket fridges. Low temperatures are prized by many scientists. Chilly experiments can slow subatomic particles down or stabilise materials in such a way that makes them easier to study, for example. This is what happens when science goes cold.

Alamy

Alamy"[We] want to be one of the technology leaders with this heat exchanger so we started developing it together with Cern," says Stefan Brohm, lead business engineer at Swep, a manufacturer of heat exchangers – devices that move heat from one fluid to another, for example. Different kinds of heat exchanger are used in fridges, heat pumps, cars and even aircraft engines to transfer heat around. In this case, Swep's heat exchangers will – once the LHC upgrade is finished – help to cool down parts of the LHC's Atlas experiment to -45C (-49F) in an effort to reduce electronics noise associated with radiation, explains Aleksa.

The specific heat exchanger Swep developed for the LHC upgrade allows for the use of carbon dioxide as a refrigerant. Although a greenhouse gas, carbon dioxide is much less potent than the refrigerant used in the previous system in question, so the changeover is an improvement in terms of sustainability.

Having developed the new heat exchanger for Cern, Swep says the same device also has applications in industrial and commercial cooling – such as in supermarket chill cabinets. "It opens up possibilities for other systems," says Brohm. Various other companies have separately developed their own carbon dioxide heat exchanger technology as part of a general trend towards less climate-damaging refrigerants.

Yifeng Yang, director of the Institute of Cryogenics within Engineering and Physical Sciences at the University of Southampton in the UK, says that many fridges, including some of the cooling equipment at the LHC, utilise the vapour compression cycle, in which a refrigerant absorbs heat and is then compressed, which raises its pressure and temperature so that the heat can be transferred elsewhere. By doing this again and again, you can cool down a room – or a giant experiment.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBut other parts of the LHC require much lower temperatures than Atlas – these regions of the collider are among the coldest places on Earth. For instance, more than 1,000 electromagnets dotted around the installation are cooled to a jaw-dropping low of 1.9 Kelvin (-271C/-456F). Below 10 Kelvin (-263C/-441F), the niobium-titanium wire coils at the heart of the LHC's electromagnets become superconductors – meaning they allow electricity to pass through them with no resistance. This ensures they do not overheat.

Achieving such temperatures takes weeks and relies on gradually cooling liquid helium down in various stages until it reaches that target temperature of 1.9 Kelvin (-271C/-456F). That's colder than even the Boomerang Nebula, the coldest known natural place in the Universe.

One key technology scientists use to reach super low temperatures that also relies on helium is called dilution refrigeration. It uses two helium isotopes: helium-4 and helium-3 – the numbers refer to how many protons and neutrons are in each atom's nucleus. Helium-4 is used in party balloons while helium-3 is one of the most expensive substances in the world. Its price fluctuates but a litre of the stuff can cost thousands of pounds, says Richard Haley, professor of low temperature physics at Lancaster University in the UK.

Low temperatures cause helium-3 to mostly separate from and float on top of helium-4, a bit like oil on water. When some helium-3 atoms are then pumped downwards into the region of mostly helium-4 atoms below them, they absorb heat in the process, which has a profound cooling effect. Haley says it's a bit like "upside-down evaporation" – a sort of inverted version of what happens when liquid water molecules change into steam and rise up from a cup of coffee. The evaporation of that water requires energy, which is why this process gradually cools down the beverage.

Unlike your coffee, though, dilution refrigeration can reach incredibly low temperatures, even down to 5-10 millikelvin.

Ultra-low temperature physics is a "frontier field", says Haley. "If you cool something down to a temperature it's never been at before, it might do something interesting." Scientists have even used low temperatures to slow down light from its usual speed of 1.08 billion km/h to just 61 km/h – where it would lag far behind cars travelling at the speed limit on a British motorway.

More like this:

• The 'very large' Hadron collider

• What existed before the Big Bang?

• How cold does it get when we leave Earth?

Some scientists use ultra-low temperature setups to study how the Universe might have behaved in the aftermath of the Big Bang, for example. And dilution fridges are crucial for quantum computers, too. The large, golden chandelier-like devices you sometimes see in pictures of quantum computers are the dilution fridges that make quantum computing possible, explains Haley. The super low temperatures are necessary because heat causes errors in quantum bits, or qubits. Qubits – units of information that can exist in multiple positions at once – are essential for quantum computing.

There are other engineering applications. Computer chips have become smaller and smaller over the years but that means imaging them has become harder. It's possible to cool down semiconductors to as low as three Kelvin in order to take sharp pictures of them for analysis or quality control purposes. "You're looking at a small area but if it's warm and expanding or contracting, even a little bit, it won't give you as clear as image," says Dylan Cawman, sales engineer at Advanced Research Systems, a company that make cryogenic cooling equipment for a range of applications.

So, if you've ever thought of a photograph as a method of freezing something in time – well, this may be the most extreme version of that you'll ever hear of.

--

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can't-miss news, delivered to your inbox twice a week.

For more science, technology, environment and health stories from the BBC, follow us on Facebook and Instagram.