ISS SOS: The plan to leave a doomed space station - quickly

Nasa

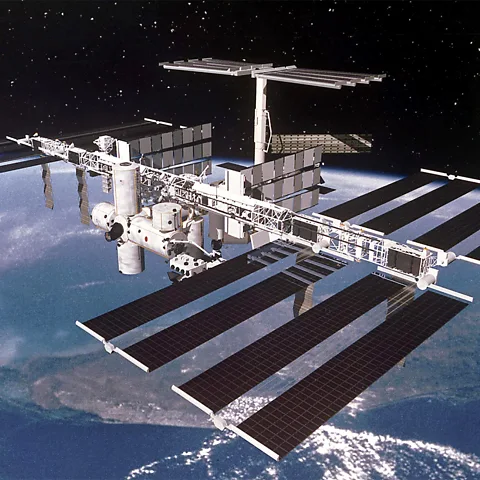

NasaAstronauts orbiting the Earth are drilled to deal with the worst possible scenarios. That includes having to leave a doomed space station – quickly.

On Thursday (15 January), the four astronauts who made up Crew-11 on the International Space Station (ISS) splashed down in the Pacific Ocean. One of the four crew members had reported a medical emergency which couldn't be treated with the space station's modest resources. Instead, they had to evacuate.

America's Mike Fincke and Zena Cardman, Japan's Kimiya Yui and cosmonaut Oleg Platonov had arrived in August 2025 and planned to stay the standard six-and-a-half months on the station. But the medical emergency necessitated the entire crew coming back together on the SpaceX-made capsule that had delivered them to the ISS.

The incident shows human exploration of the Solar System, even in low orbit, can never be considered routine. "Space," said Dr McCoy in a recent iteration of Star Trek, "is disease and danger, wrapped in darkness and silence". And that is on a good day.

Imagine being woken by a persistent blaring siren. Disorientated, you are sealed in your sleeping bag in a tiny space station cabin. The oxygen is being sucked away through a hole in the wall punctured by space debris, or maybe toxic ammonia is seeping into the air around you. Perhaps flames are licking at the doorway.

If you are a trainee astronaut, you don't have to imagine any of these things – you will have experienced every one of them – and possibly all at once – many times in an International Space Station (ISS) simulator on the ground.

"They'll throw you in the deep end," says Meganne Christian. She is the senior exploration manager at the UK Space Agency, Christian is also in training as a reserve astronaut for the European Space Agency (Esa).

"They won't tell you what's going to happen – for example, fires, ammonia leaks, all sorts of different things and you just have to deal with them," Christian says. "It's designed to be a situation that will never happen, fingers crossed, but it's really to get you ready for the idea that lots of things could happen at once and you have to be able to make decisions on your feet."

SpaceX

SpaceXBeing able to keep it together under pressure is a key consideration during astronaut selection.

"They questioned us thoroughly about it during the interviews we had with psychologists, and during the practical exercises we did in teams or in pairs," says Christian. "They are looking for people who can remain calm in those situations and are adaptable and resilient."

Ever since the first men and women left the Earth, mission planners have been considering what happens when things go wrong. In 1966, for example, Nasa commissioned the Rand Corporation to carry out a nine-month study into "contingency planning for spaceflight emergencies."

Covering everything from flights in orbit, to lunar exploration and even missions to Mars, researchers examined threats to life including medical emergencies, oxygen deprivation, chemical and radiation exposure. They recommended designing spacecraft with multiple back-up systems and incorporating modules designed to carry the crew back to Earth in an emergency. The findings of that report informed the Apollo and Space Shuttle programmes and are just as relevant today.

"The fact that you always have a ferry ship ready to take you home at almost a moment's notice is a basic rule that all spacefaring nations use," says Jonathan McDowell from the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Cambridge, Massachusetts and author of Jonathan's Space Report. "You never have to call for a taxi – you always have one right there if your space station gets damaged."

This works fine until that spacecraft is itself the subject of the emergency – a situation recently faced by the crew of the Chinese Tiangong space station. In November 2025, the taikonauts discovered that their spacecraft windows had been damaged by a fragment of orbiting space junk. Mission control had to send up a replacement capsule.

The other limitation of this system is that if only one crew member is sick or injured then the whole crew of that ferry spacecraft has to return – which the current ISS crew know only too well after one astronaut experienced a medical emergency on the station.

Nasa

Nasa"You have to keep everyone together and bring the whole crew home," says McDowell. "Otherwise, you've left them there without a ride home and you don't want to do that."

This unprecedented evacuation of an ISS crew took place in an orderly manner over several days. But what happens if astronauts need to get off the station quickly? In her book Back to Earth, astronaut Nicole Stott describes the mantra astronauts live by as "go slow to go fast."

"We've all had situations in our lives where if we could go back and do it differently, we wouldn't have freaked out as much about something or gotten so wound up that we lost sight of what the problem even was," she told the Space Boffins podcast. "Everything doesn't have to be fast, it just has to be done at the appropriate time and appropriate speed to allow us to digest what's going on and respond effectively."

In practice that means reacting to the alarm, assessing what's gone wrong, following the checklist and dealing with the issue methodically as a team. A fire, for instance, would mean locating all the crew, putting on respirators, activating fire extinguishers and sealing-off modules.

"You've trained so much that you just know, 'OK, I have to immediately do these in response to this alarm that's going off'," says Stott. "There are things you know you just need to immediately to do to make safe the situation, take care of all of your crewmates and make sure that no one's left behind – you don't do yourself any favours if you're freaking out."

So, within minutes of an alarm, the crew can get to their ferry spacecraft, seal the hatch and assess the situation.

"The escape capsule is not only an escape capsule, it's also your safe haven," says Christian. "From there you can perform different kinds of procedures like going in with respiratory equipment to check different areas of the space station, if you find that you have to leave the station, then you can do that."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWorst case scenario, the crew could be back on the ground in a matter of a few hours. But with missions planned to the Moon and Mars, that will no longer be the case.

"You're talking at least three or four days from the Moon but when we talk about Mars, you're going to have to wait two years for the next bus," says McDowell.

"You're going to have to accept a higher level of risk, and you have to have more extensive medical equipment and medical capabilities with you – a hospital module and not just a first aid kit," he says. "I think that this latest event with the ISS crew is going to spur Nasa to take a new look at that."

Christian has already experienced what the isolation of Mars might be like during her two missions to the Concordia research station in Antarctica. Located on an isolated plateau of ice near the South Pole, the French-Italian base is completely cut-off in winter, making any emergency rescue all but impossible.

"We had to be very self-sufficient but we had a doctor on the crew, and a small hospital," Christian says. "We also had a second base area that we could evacuate to if something happened to the station and did a lot of simulations to make sure that we could make that second base in an emergency."

Meanwhile, with the ISS due to be abandoned in the next five years, researchers are revisiting the idea of space rescue. First highlighted in that 1967 Rand report, it came to the fore during Apollo 13 and was demonstrated during the 1975 Apollo-Soyuz mission when Soviet cosmonauts and US astronauts docked their spacecraft together and shook hands in space.

More like this:

• A fiery end? How the ISS will bow out

In a 2021 research paper senior project leader at The Aerospace Corporation's Space Safety Institute, a government funded non-profit organisation based near Washington DC, Grant Cates highlighted what he termed the space rescue "capability gap". He was concerned that if a commercial spacecraft got into trouble, there would be no one to come to the rescue.

"Do we have the procedures in place to carry out a simple rescue if our spacecraft are somehow unable to bring our crew safely home?" Cates says. "You could think of it as needing a towing company – what we're trying to avoid is a situation in which we have an emergency in the next few years in which don't have a capability."

Esa

EsaWhat that means in practice is always having a spacecraft available on the ground that is ready to go – like the Chinese had with Tiangong – and universal docking adapters that mean any nation, or commercial company, can use their spacecraft to come to the rescue. There might even be companies dedicated to maintaining orbiting space capsules and providing a breakdown service. Cates' latest research is in partnership with the Rand Corporation – still studying the problem 60 years on.

As for missions to Mars, to improve safety, Cates envisages sending a fleet of spacecraft. "This is how the great explorers went about the world on the oceans, right?" he says. "They didn't go typically with one ship, they sailed with multiple ships so that if one ship had a problem, you could transfer the people and supplies to the other remaining ships and get on with the mission."

But already the risks are ramping up. In the coming weeks, Nasa plans to launch its Artemis II mission. The mission will take astronauts beyond the Moon for the first time since 1972. The spacecraft is just a single capsule, there is no spare ready on the ground and – once beyond Earth orbit – no possible evacuation plan. If anything goes wrong, it will just be them, mission control and the darkness and silence of space.

--

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can't-miss news, delivered to your inbox twice a week.

For more science, technology, environment and health stories from the BBC, follow us on Facebook and Instagram.